To do or not to do a Ph.D.?

- Meha Jadhav

- Sep 4, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 10, 2022

This article is for those of you just starting out a Ph.D. or are thinking of doing one. Here, I will tell you what it means to do a Ph.D. and whether it is the right step for you or not. I hope the points I highlight will help clarify your doubts and help you reach a decision.

The first thing to note is – A Ph.D. is unlike any other degree you have pursued. It doesn’t have a ‘structure’ i.e there are no fixed courses, lectures, or hours that you have to complete to finish a Ph.D. Because of this, each person’s experience in Ph.D. is very unique. It also means that the duration of a Ph.D. varies a lot (it can take anywhere between 4- 7 years on average). I will outline a general format followed by most Indian institutes and universities. It is also more relevant to a Ph.D. in biology; though I think the structure for other sciences is also similar.

The not-so-straight path to a Ph.D.:

You can join an institute or university for a Ph.D. in two ways: one is through a graduate program and the other is by directly contacting a lab head.

I took the first way, which has the advantage of lab rotations. In the first month of joining, my batch was given an overview of the different labs and their research at the institute. After this, we had lab rotations in two different labs of our choice. I spent 8 weeks in a lab working on a short project. It gave me time to learn more about the various projects in the lab, the general lab environment, and the supervisor’s mentoring style. These experiences helped me make a more informed choice.

In the second way, you directly write to a lab head you want to work with. In some cases, you apply to an institute graduate program, and by the end of the application process, you are assigned a lab based on your preferences but without a lab rotation. In this case, you have to put in some thought even before applying to the institute and narrow it down to at least 2-3 labs that you may want to join. Here, you do not have the luxury to figure out which lab works for you later.

Alright, so say you have done all this and now you have officially joined a lab. What’s next? What do you do with a Ph.D.? The main goal is to perform a substantial amount of original research. By original research, I mean research (discovery, tool development, etc.) that has not been done by anyone before. What counts as substantial is subject to the discipline you choose, your institute’s policy, etc. For example, I require one research article, in which I was the lead author, published in an international journal to submit my thesis.

As you must have realized, choosing a topic of research is difficult, especially when you are just starting out and are not familiar with the developments in your field of interest. Usually, this process takes some time and you and your supervisor will develop this over many discussions.

In your first year of your Ph.D., you will also have to take some courses, making you juggle between attending lectures and working in the lab. Once your course requirements are done, you are now free to give all of your working time to the lab and your research. Typically, you will have to work towards your research project for another 3-5 years.

Somewhere towards the end, you will summarize your findings into one or more research articles. Finally, the thesis is reviewed by other scientists, you present it to the others in your institute and also have a viva and voila! You have a Ph.D.!

Wait! There’s more…

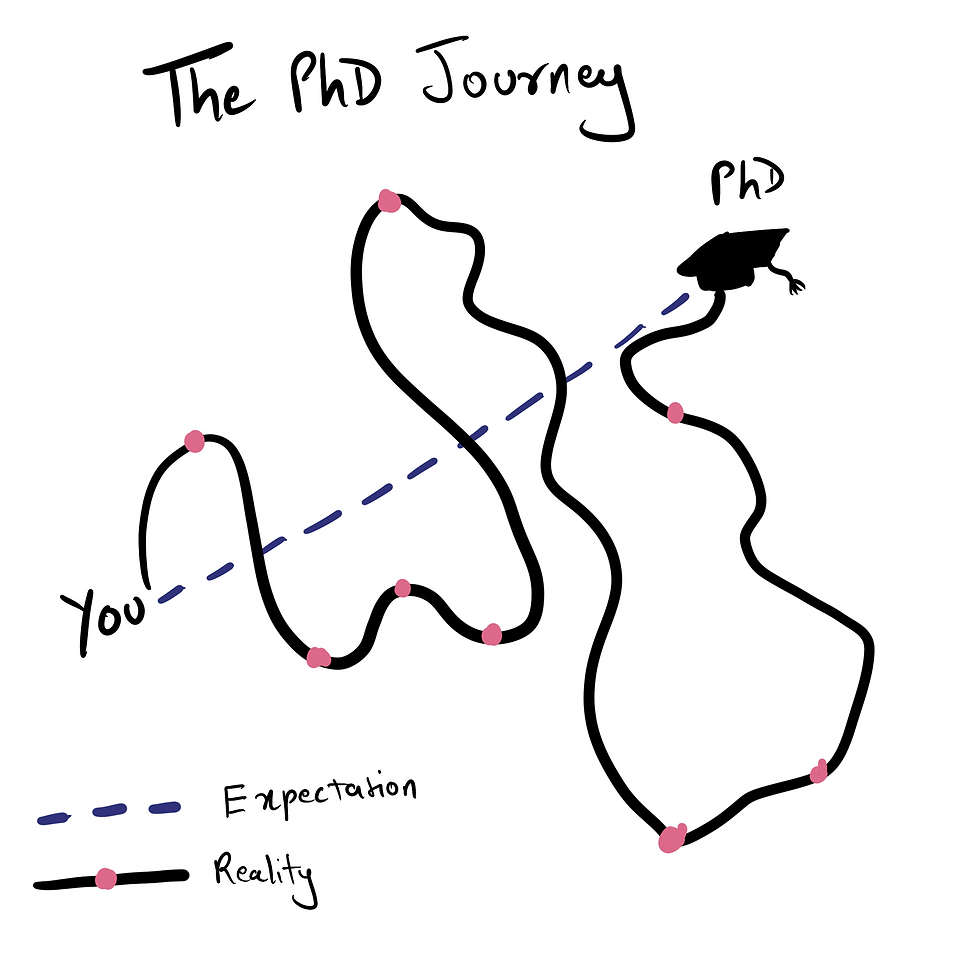

That sounds quite straightforward! Then why do people take a long time (5-7 years) to do a Ph.D.? Because what I outlined above is an expected course of a Ph.D. degree. In reality, you will face many hurdles and you may have to sometimes take a different route or even take a few steps back to move ahead!

Doing research requires you to delve deep into a field. Gaining mastery over certain critical techniques, programs, and analyses as well as a thorough understanding of the scientific literature can take many months; if not years. The kind of experiments you will do in your Ph.D. will be much more complicated than your standard course practical. Sometimes experiments fail and it takes a long time to troubleshoot. You may also be forced to change your research question because the experiments disprove your hypothesis or because the experiments needed are not feasible. There can also be delays in publishing your research article and until that is done, you may not be able to submit your thesis. If you are very unlucky, your supervisor may not be ready to let you go and they may want you to stay back and do more research in the lab. These are just a few of the things that regularly cause delays.

As a graduate student in a lab, you will handle many additional responsibilities like teaching courses, training, mentoring new members, maintaining instruments, ordering lab supplies, etc. These also take up a large chunk of time.

Is a Ph.D. meant for you?

Have I managed to convince you that doing a Ph.D. is nothing like pursuing any other degree? It also means that not everyone is going to like this experience. So here is my advice for you: think carefully before you sign up for a Ph.D. program. Figure out your long-term career goals and whether having an additional degree will help you reach them.

If you are very passionate about science, want to be a researcher (in academics or in the industry), are not easily ruffled by a few failures, are resilient, persistent, and can work consistently towards long-term goals without constant supervision, then doing a Ph.D. may work out for you.

But please DO NOT start a Ph.D. if you just want a ‘Dr.’ in front of your name, or because you have no clue what else to do after a master’s degree, or because you applied for a Ph.D. program and got in or because many of your batchmates are also applying.

You might notice that I have not mentioned intelligence as a criterion for pursuing a Ph.D. In my opinion, hard work and consistency are more crucial than intelligence. Also, intelligence doesn’t guarantee you will do well in Ph.D.

You can gauge for yourself by working in a lab for some time. Apply to summer internship programs during undergrads and masters’. This way, you get to spend 8 weeks working on a small project in a lab. You can also go for a longer trial right after your master’s. Join a lab of your interest as a JRF or research assistant for a year and see for yourself.

Most important: talk to people! Get in touch with people who are already pursuing Ph.D. to know more about their experience. All of this will tell you what you need and whether doing the Ph.D. is the right decision for you.

Comments